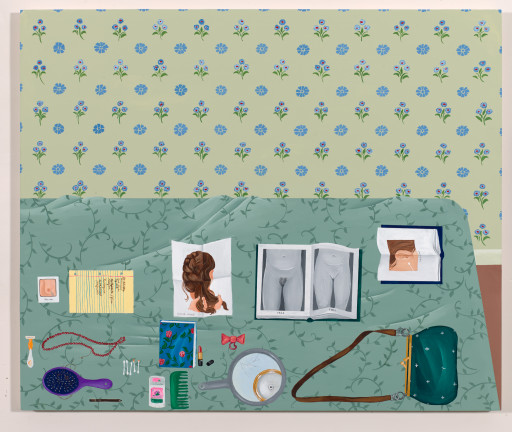

Everything tends towards entropy. Growth becomes overgrowth and then decays. Facing life’s countless tangled messes, the need to take care of oneself, one’s home, and one’s dependents is always present, or fast approaching. Making and keeping order is real, typically gendered work, and such maintenance work is constant, setting the pace of daily routine in ways both self-sustaining and exhausting. As divergent portraits of life as it’s lived, Sarah Miska and Anne Buckwalter’s paintings gathered in “Upkeep” show female hygiene and regular grooming to involve lots of brushing, washing, trimming, tucking, conditioning, shaving, plucking, and tying. It signals itself through a great many familiar appurtenances like tweezers, razors, combs, brushes, toothbrushes, soap, sponges, scissors, needles, brooms, dustpans, rags, laundry and waste baskets, pills, hair ties and scrunchies, nail polish, Band-Aids, pads, tampons, condoms, deodorant, boxes of Kleenex, mirrors, and tubs of Vaseline. It has a lot to do with cleanliness, but also culturally-specific conventions and the appealing appearance of total bodily control. Grooming conventions may be coded or seem arbitrary, but can belie health advantages, like dental hygiene correlating to longevity. Upkeep is not only life- and culture-sustaining, it’s also just a basic part of being an adult in the world, taking responsibility for oneself and the things we care about. And, concerned as it is with appearances, it has an inherent investment in aesthetics and the decorative, making it an aptly self-referential subject for painting.

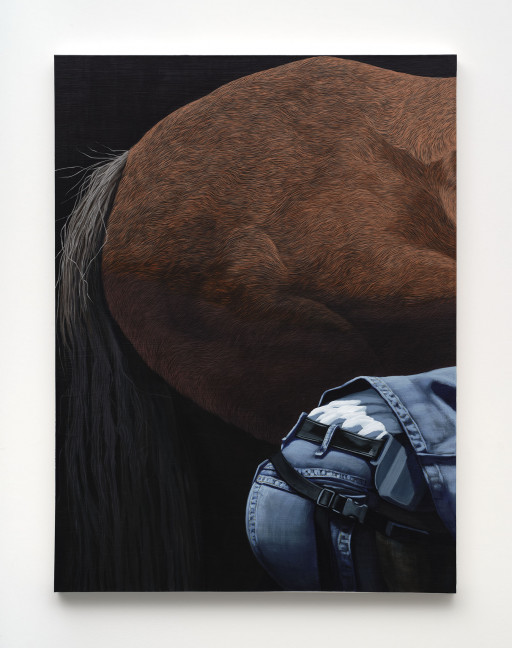

Both artists construct their own distinctive imagery, narrative sense, and technical facture to revolve around questions of control and a heightened attention to detail. Single errant strands of hair springing from a perfect bun, a length of looping floss on the tiled floor, a used Q-tip soiled with yellow wax, individuated bubbles dispersed in a sudsy lather, perfectly glossy pink nails, the wavy directional cowlicks of hide charting the topography of muscle. Active care-taking, especially when aimed at the self, requires paying attention, noticing small things that need attending to or fixing. Being highly sensitive. Looking up close. Such magnified focus manifests through close cropping, extreme proximity, hyper mimesis, and enlarged scale in Miska’s horse paintings, or in the modest-but-ornate interiors filled with tons of tiny, elaborate, titillating details that pull you into Buckwalter’s demur scenes and often make me laugh.

Curiously, for both, the ideas that make upkeep so compelling, from an aesthetic and labor point of view, are epitomized by braiding. In fact, depictions of hair (short or long, horse or human) and its tidying up into braids constitute their own major subgroup of subject matter shared by the artists, emblematic of great care and pride taken in bodies and their well-being. Miska’s Plaiting Needle (all works 2024) visualizes precision in image and execution—meticulous, fastidious devotion to both horse and painting. Hair and hide warm the core logic of her visual world, being the implicit if not explicit subject of nearly every painting. More broadly, both artists have a fascination with texture and pattern. And while Miska’s sensibility is tied to her love of Domenico Gnoli’s similarly large, closely cropped, and detailed studies of fabric and hair, Buckwalter’s infatuation with flat decorative pattern emanates from her Pennsylvania Dutch upbringing and aesthetic immersion into that tradition of interiors, furniture, quilts, wallpaper, ceramics, and textiles. The variation, extent, and exuberance of Buckwalter’s floral and geometric patterns, crammed in edge-to-edge, across walls and floors, are entrancing and reinforce the folk art and fairytale quality of her weirdly flattened, shadow-less rooms. Each artist in her own way understands surface pattern as defining space.

Whether by Miska’s cropping or Buckwalter’s strategic mirror reflections—or both artist’s affinity for bodies seen from behind and largely occluded—there is an avoidance of direct, frontal depictions of people. And by avoiding depictions of whole faces, there is always a crucial sense of meaningful withholding—a turning away and guarding of some privacy, concealing identities. Objects get cut off abruptly or poke shyly in at the pictures’ edges, making the frame and border regions especially charged and suspenseful. Both artists are so thoughtful and deliberate about framing, puncturing illusionism with reminders of the inherent abstractness of paint on ground. Knees or a bit of red cloth activate the perimeter and internal edges inside Buckwalter’s interiors; parallel bands of decoration at top and bottom make a frame while also advancing narrative space; a toothbrush in a glass balances along the bottom edge of Medicine Cabinet, while half of Miska’s Trimming and Shoeing painting makes a cameo in the mirror reflection. (There are winking nods to Miska’s pictures and Easter eggs tucked throughout this group of Buckwalter’s paintings.)

Whatever might lie beyond the frame becomes implied presence, just as the pictures mostly describe human presence indirectly through other things. Their shared oblique relation to picturing living subjects is a key factor in the particular sense of drama each artist builds into her pictures. Miska’s pictures have the high drama of black backdrops, lush cinematic close-ups, vivid clarity, and theatrical spotlighting—behind the scenes of power and history. Buckwalter’s have the stage drama of naturalistically composed set design: an oddly spare and excessively patterned domestic interior with choice details carefully positioned as telltale props and narrative clues. Hers is the drama of psychological space, intimate relations, unspoken or whispered things, and going to the bathroom. Together, theirs are the dramas of being drawn in and getting too close, of permeating light and the stuff of female fantasies that gets left out of storybooks.

– Sarah Lehrer-Graiwer