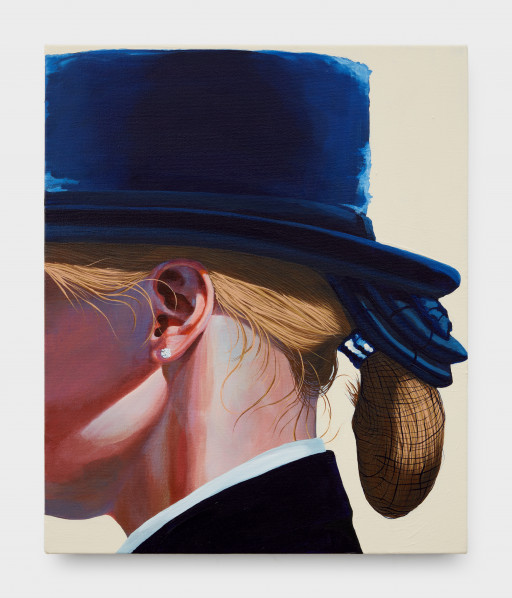

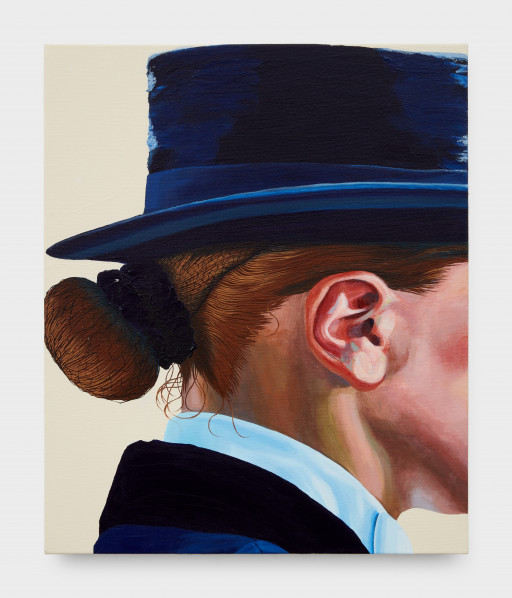

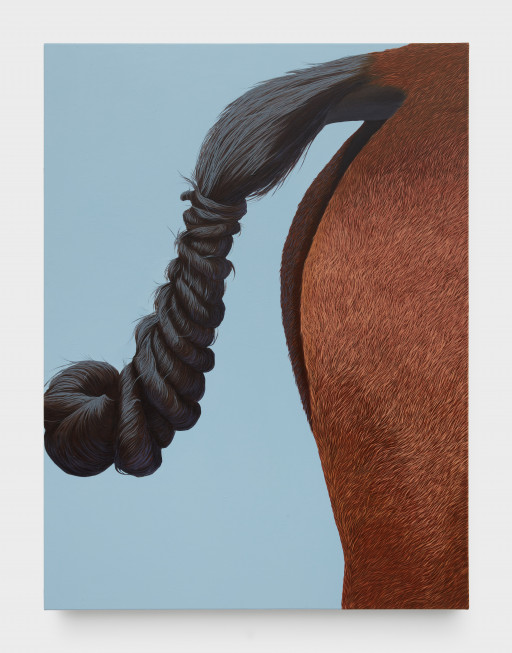

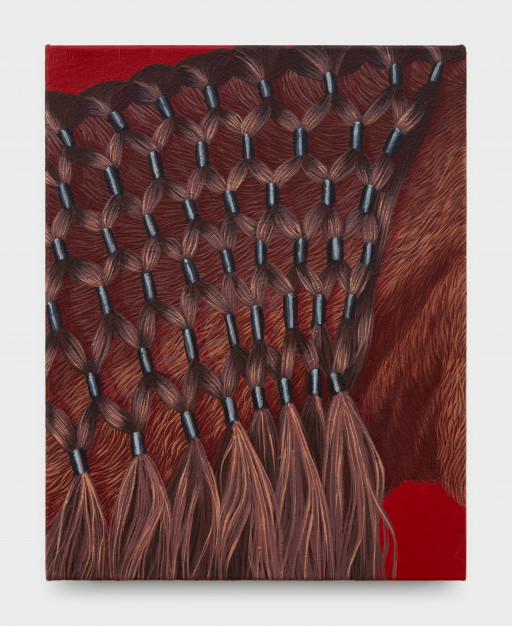

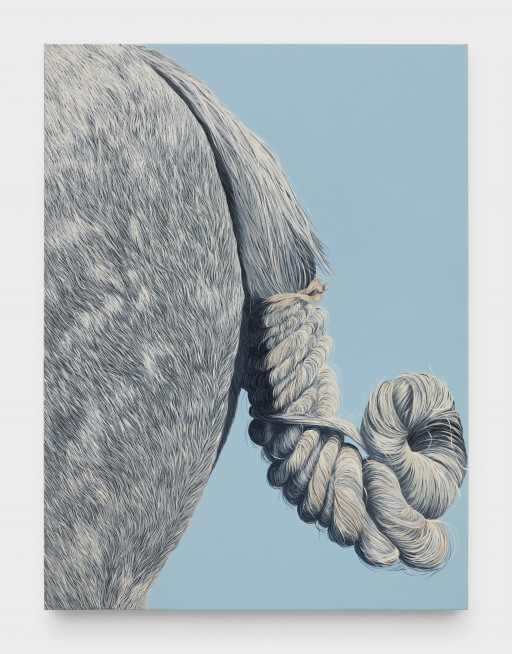

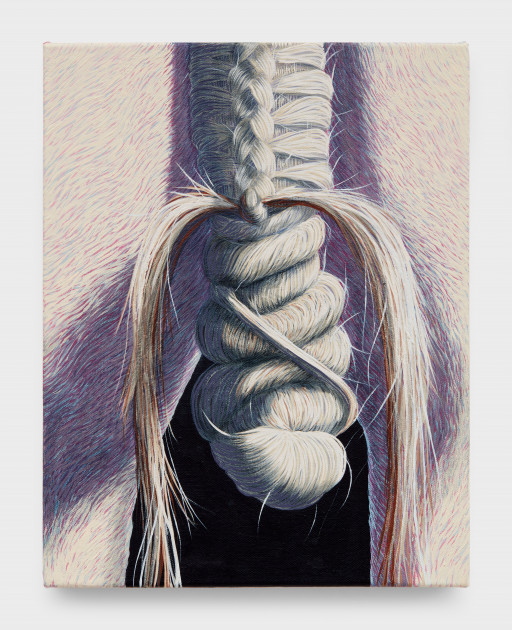

Presenting a glimpse into the world of equestrian competition, Sarah Miska’s recent body of work continues an ongoing study of the social and aesthetic dimensions of horse riding. In Tidy, Miska depicts the sport’s more inconspicuous details—a plaited horsetail, a glossy black hoof, or a rider’s bun—through magnified and oblique views that evade any semblance of a whole. We are presented instead with partial backsides, uneven profiles, and close-ups of subjects in a perpetual state of turning away. Often these fragments are depicted at an inordinate scale, as larger than life representations awkwardly cropped but still brimming with meticulous detail.

Hair, and more specifically, the various ways by which it is constrained, is a dominant motif. Both horse and human hair (at times, indistinguishable) are treated with formal and psychological scrutiny. Bound and constricted by a proliferation of elaborate braids, bows, and nettings, hair is the site where the otherwise immaterial power relations of horse and rider most explicitly manifest. Equestrian sport is, of course, a practice informed by the discipline and control of bodies, one that nevertheless prioritizes a “natural” synthesis between horse and rider.

Likening the training methods of classical dressage to the socio-cultural conditioning that takes place in capitalist society, it was Henri Lefebvre that described human socialization as a cyclical and repeatable sequence of “imperatives and gestures.” For Lefebvre, repetition informs the means by which humans are broken in like animals. While Miska’s paintings zero in on the material nuances of subjugation as both a mode of decoration and a source of pleasure, it is the recursive labor involved in their making that evoke power relations beyond the site of equestrian sport.

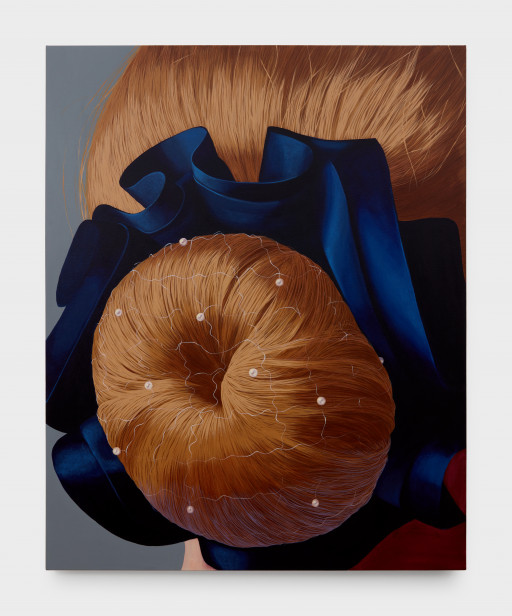

In Pearl Hair Net, a rider’s bun fills the entirety of a 5’ x 4’ canvas and every element of the composition evidences a precise and methodical hand. From the reflective sheen on a scattering of pearls adorning a delicate hairnet to the individual strands of hair escaping it, each detail reveals a fastidious, obsessive, attention. Yet, even with this profusion of detail—and the intimacy that such visual proximity suggests—these images remind us that the world and wealth they signify remain inaccessible to most.

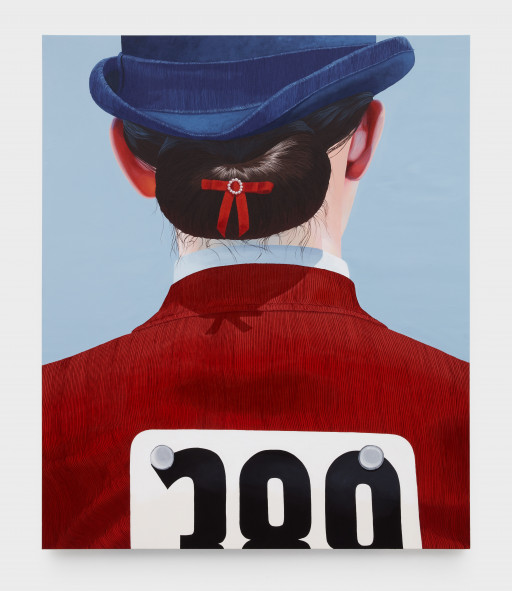

Likewise, in Tidy Bun, we are presented with a fragmentary view of a rider’s posterior. It is not the shape of the rider’s orifical bun that renders the image obscene, but the care that has gone into the tiny and painfully ineffective red bow adorning it. Each individual groove of the ribbon and the subtle reflections on the ring of pearls at its center is painstakingly rendered. As are the strands of hair that frame her neck and the ridged surface of her coat. Despite the diminutive size of these details, they fill the canvas with a sinister excess, enveloping us with an almost claustrophobic intensity. In all Miska’s paintings, we are confronted with the tension between the immediacy of the image and the intrinsic exclusion subtending it.

We are drawn to these inconsistencies, and to the vexing details. An awkwardly cropped stock tie. The tendrils of hair that have escaped the braids of an otherwise controlled coif. The reflective gleam on nail heads binding hoof to horseshoe. One finds perverse pleasure in what is askew, the elements that have fallen out of place, or are purposefully overlooked. The spaces and minutiae that will always need tidying.

— Olivian Cha