Painting condenses and fixes this human time of rushing decades that is otherwise evasive, untouchable.

— Czeslaw Milosz

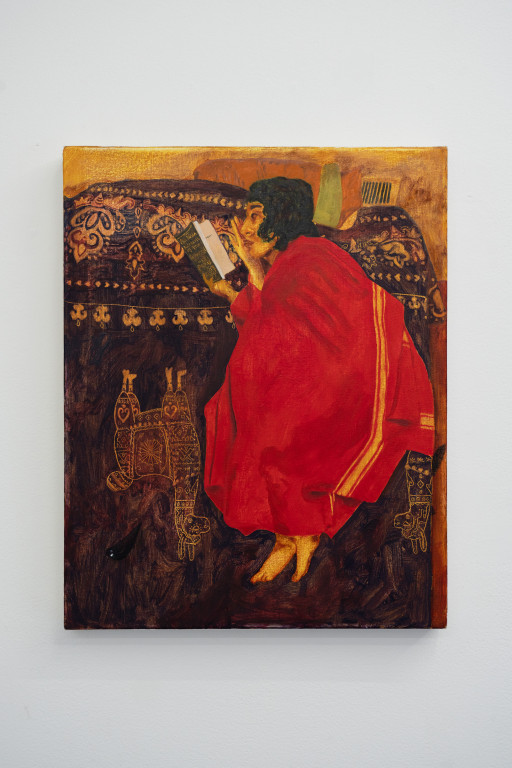

The figures in Pachi Muruchu’s paintings are otherwise engaged. Deep in thought, in a book, in a memory or idle conversation, his subjects inhabit durations that exceed or resist the demands of capitalist time. They reside in dreamy or melancholy hermetic interiors, where plants and birds—borage and red-bellied trogon—are braided into the environment, surreal, but unacknowledged as such. Each of his scenes is invested with references that are kaleidoscopic in their scope. We see elements from botany, mythology, European genre painting, and Andean art traditions; we see books on resistance movements and postcolonialism. The resulting canvases offer a kind of patchworked history painting, or better, ahistorical painting.

At the heart of Muruchu’s work is a desire to access an animistic relationship to contemporary urban life. He seeks a return to what he has described as a “materialist subjectivity” that is latent beneath colonial ideologies. How can one learn from ancestral knowledge and indigenous cultural labor while reckoning with one’s own responsibility to struggle against occupation, he asks. Can one decolonize subjectivity to arrive at a perspective that grants respect and curiosity to nature, to inanimate objects?

Muruchu is Kichwa, and his family is from pueblos in Azuay, Ecuador, but he was raised in Spanish Harlem. As he grew up in the 2000s, he was aware of the Lenape whose land his building occupied. He lived alongside Caribbean and Latinx neighbors, who lived alongside pet iguanas and cockatoos. Muruchu’s work finds him revisiting his own family’s histories and rituals, those that have been neglected or compromised due to migration. Family members on his maternal side were curanderas, or healers, with an intimate understanding of the medicinal properties of plants. In his paintings, he integrates these various contexts, evincing a sense of place that is complex and indivisible.

Take Tsinikuna (♫The West is gonna perish ♫), 2022, named for the Kichwa word for stinging nettle. A man in loungewear reclines on an Indian textile, whose bold pattern enters an ecstatic dialogue with the man’s tattoos, his bandana, potted plants—the titular nettle, which was used by Muruchu’s family to aid those suffering from arthritis—and posters that reference the work of Emory Douglas, Faith Ringgold, Spike Lee, and Jacques-Louis David. The pictured man reads civil rights activist Derrick Bell’s 1992 book Faces at the Bottom of the Well, which calls out the inherent racism in American society. It is perhaps by contrast, then, that we recognize the painted subject’s posture, propped on his side to face the viewer, as that of an odalisque. Muruchu upends the orientalist art historical genre, which traditionally featured an enslaved woman or concubine, recasting the objectified figure as a subject consumed with their own interiority, healing them in this way.

Muruchu approaches the canvas with an airy naturalism, capturing the exact weight in the slump of a shoulder, but setting flesh aglow like leaves before sundown. His handling of the figure recalls a para-trajectory of painters who have similarly engaged history painting to radical effect. There is something here of Leon Golub, whose brutalized realism drew on Greek and Roman art to report on the banality of evildoers in the Second World War and in Abu Ghraib. Elsewhere there is Martin Wong, whose dystopic East Village New York cityscapes offered a romantic inquiry into the codes of communication among marginalized communities. There are passages that recall Kerry James Marshall’s exacting spatial complexities, patterns, and symbols. Each of these painters has nurtured a poetics of the mundane, developing nuanced iconographies that may be liberating or alienating for the viewer, because they reflect the vocabulary and references of a particular community.

The glow that is specific to Muruchu’s paintings results from a monochrome ground that serves at once to abstract his scenes ever so slightly and embrace them in cohesion. He determines the color that will unite the image this way by selecting one depicted object that has distinct poetic intensity. In Wawkikuna II (El sendero luminoso), 2021, or Brothers II (The Shining Path)—a painting that meditates on the harshness of the urban environment to non-white men—that object is George Jackson’s 1971 book Blood in My Eye. Its hue casts an uneasy marigold warmth across the painting. Jackson wrote the book in San Quentin, where he was imprisoned indefinitely for stealing seventy dollars from a gas station. During his confinement, he joined the Black Panthers, studied revolutionary theory, and became an organizer. Ultimately, he was murdered by prison guards. For his exhibition at Friends Indeed, Muruchu sought to engage the local context and account for his own relationship to San Francisco, even if he was painting interiors, even if the topics he broached were not specific to one city or another. Here, Muruchu asks us to hold disparate elements together, but to still behold their distinctions. In this way, we might make space for different ecologies of perception and knowledge.

— Annie Godfrey Larmon