Opening: January 14, 5-7pm

Show run: February 20-March 17, 2023

Curated by Aleesa Pitchamarn Alexander, Ph.D., Robert M. and Ruth L. Halperin Associate Curator of Modern and Contemporary Art and Co-director of the Asian American Art Initiative, Cantor Arts Center, Stanford University.

The first solo exhibition of New York City-based artist Nina Molloy is now on view at Micki Meng at Four One Nine in San Francisco. In this debut presentation, Molloy explores the historical, spatial, and ontological possibilities of painting as they relate to her specific experiences as a Thai American growing up in Bangkok. The results are richly textured portals that insist on the permeability between past and present, painted surface and subject, and memory and mythology.

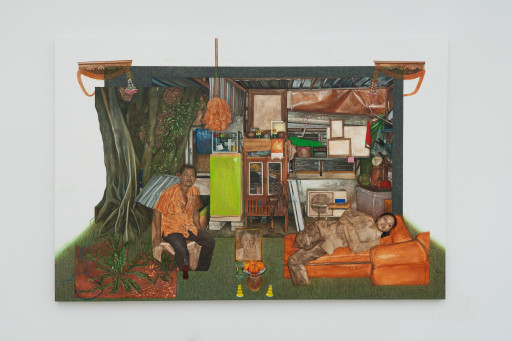

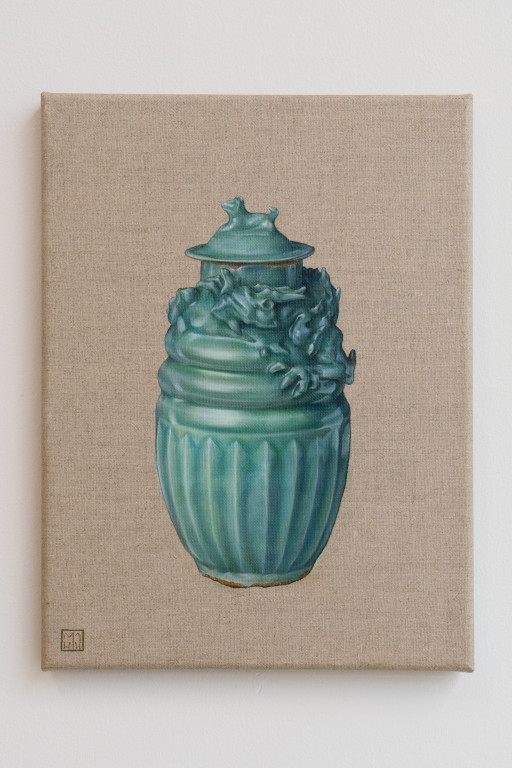

Molloy takes the vernacular architecture of San Phra Phum, or Thai spirit houses, as a conceptual and formal launch point. Spirit houses are small devotional structures and omnipresent sights/sites in Thailand, lodging ancestral spirits of the land and producing them. We must appease these ancient spirits so that they may protect us in the present. Molloy enlarges these doll-sized houses, blowing them up into monumental history paintings that reference the personal and art historical.

In Shrine, Molloy evokes the collapsed perspective of Robert Campin’s Annunciation and pays homage to the visual density of Martin Wong’s urban landscapes through her representation of intergenerational haunting. Objects of personal significance are barely contained within the frame. Molloy’s great-grandfather, grandfather, and mother are rendered in various states of translucency, their amorphous boundaries blend bodies into objects. They are visual and psychological ghosts—floating on the foreground of the picture plane, as much a part of the painting’s world as our own.

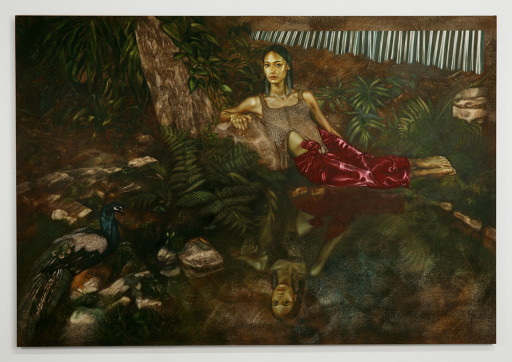

Corrugated sheet metal, a material widely connected with the Global South, appears in Shrine, Shrine Study, and Nang Ta-Khian. Molloy elevates this material, often associated with poverty, displacement, and lack of infrastructure, to the status of a precious element. In her paintings, sheet metal sparkles within the verdant lushness of Thailand’s tropical landscape, existing alongside peacocks, orchids, and tualang trees. The artist draws on animist Thai folklore, materializing the water spirit Nang Ta-Khian in painted form, but locates her paintings within the contemporary moment. Bangkok, after all, is a city of commingling opposites: containing the secular and religious, natural and urban, ancient and post-modern. Molloy’s paintings are syncretic visual collisions of these attendant contradictions: San Phra Phum for the modern world.

Molloy’s unique iconography is immediately legible to me, partly because our life stories contain multiple parallels: our white American fathers met our Thai mothers while traveling in Thailand (my father in the 1980s, Molloy’s in the 1990s). Both of us were born in Bangkok and spent significant parts of our lives there. Though of different generations, we belong to a particular diaspora—luk khrueng living outside Thailand. Encountering Molloy’s paintings for the first time was like seeing my most intimate and distant dreams made hyper-visible, rendered with extraordinary, surreal detail (White Elephant Procession as case in point). We are also both students of art history. Molloy’s attention to the formal and historical traditions of oil painting imbues her works with spiritual forces that both express and exceed our individual experiences. In Molloy’s works, I see the collapse of the psychic, geographical, and generational divides that separate me from my motherland. In other words, her paintings are another place for me to call home.