Putrefaction

Candice Lin & Miljohn Ruperto

Candice Lin: Maybe as a start we could talk about why we both separately in the past were interested in Bernard Palissy and in ideas of spontaneous generation and putrefaction?

Miljohn Ruperto: I got interested in a decoupling of God and Life in Palissy’s project because Palissy’s primacy of the mineral disrupts the hierarchy and Great Chain of Being by rendering once living organic matter into stone-like earth that has been fired, mimicking geological processes in the kiln.

CL: Yes, one thing I always love in ceramics is the way that it makes you rethink categorizations of matter and hard divisions between inanimate and animate life. Clay is essentially rock that has been decomposed (yes, ceramics and geology books use that terminology!) by weather (wind erosion, sun heat, moisture, freezing). Our dead bodies become in part limestone from our bones, plants become jet, a lignite/type of coal that is also a gemstone but not a mineral one but a mineraloid because it is what happens to wood that has become petrified from extreme pressure. I love thinking about the still visible aspects of lives that were lived out in different bodies now becoming the new body of the stone. Thinking about intergenerational and epigenetic theories around memory it makes me wonder and apply these ideas across geologic timespan: what then would be that stone’s memory? Would it remember when it was plankton? A redwood? It is the unfathomable-ness of stone’s timeline and our sense that stone does have memory that makes us come up with theories like the Stone Tape Theory, popularized in the BBC film The Stone Tape, the idea that hauntings and ghosts appear when traumatic histories (lodged in stones) get released through disturbance of the stones (through architectural renovations, digsites, etc.). Richard S. Shaver also used to saw very thin slices of stone that he would project light through and make drawings of the projections, trying to see the images and historic scenes embedded in there, excavating a rock “slideshow”..

I also really love how ceramics replicates geological processes of transformation (the heat and pressure of the earth’s magma and gravity–organic bodies becoming stone becoming clay that is then shaped by organic bodies (us haha) and fired in a kiln to cone 10 to become vitrified like stone.

Palissy himself somewhat humorously materialized this analogy between kiln and organic process. During the establishment of his final workshop “Montpalissy” at Sedan, he specially commissioned the construction of a ceramic oven in the shape of an enormous craggy rock. This stony oven alluded to the generative potential that Palissy perceived in the mineral world itself—especially around ponds, caves, and grottoes.

MR: I think Palissy’s creation of a self-enclosed cyclical nature outside of a Christian hierarchical operation where God creates life is really interesting. This enclosed cycle, based on heat, water, and mineral, becomes recursive looping pockets within the Great Chain of Being where life and death cycle through independently, away from the directedness of a cosmic will.

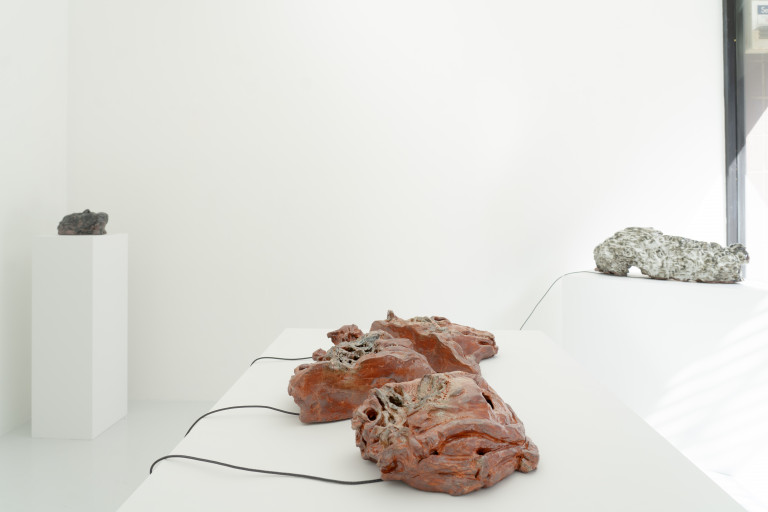

In our sculpture, The Corpse, predator and prey merge together into a single unit, entrails, bones, skin, merge together in putrefaction. This decaying then slows tremendously, shifting this operation unto another temporal register, the geological, when fossilized. In death, both animals become one being. Were they always one being? The Corpse was formed by hand, then scanned through photogrammetry and re-assembled in digital space. There it was scaled up and merged with other digital components. It was then 3D printed in clay then reformed by hand. Is the digital an expression of the mineral, as Esther Leslie conjectured?

CL: Can you talk a little more about what Esther Leslie’s idea of the digital as mineral is about? It’s intriguing, if we think about how the digital aspects of our life are these processed and reprocessed forms of organic matter taking other forms, but what did Leslie mean by this?

I also love the idea that these sculptures, like fossils in nature, are not necessarily inanimate negative spaces and trace matter (iron oxide and other minerals) left by once living organic matter, or illustrations prioritizing once living organic mammalian life, but that they might be alive currently but at such a slow pace we can’t perceive it.

MR: I like to read Esther Leslie’s idea of the digital and mineral as a separating of human intention from digital processes. When we scale up our temporal and spatial measure, we can watch, like aliens or angels, the Earth’s geological processes continue through the human, through sand and metal, like electric current through circuits. The digital is just the mineral expressing itself.

Leslie, Esther, Synthetic Worlds Nature, Art and the Chemical Industry, Reaktion Books, 2005

CL: I’m also curious if you could talk a little bit about your past work that you did on Palissy before we realized we were both independently researching and interested in his legacy. You had worked with some people at UC San Diego to 3D scan snakes moving and wanted to 3D print the motion of life, as a kind of new approach to Palissy’s desire to capture life through killing it. Can you talk about that project and how it led us to this current sculpture, Rolling Head (durational collapse), of John the Baptist’s head rolling down a hill, which is based on an animation you made.

MR: I tried to figure out a viable way to follow Palissy’s efforts. I came across a Jean Arp sculpture called Snake Movement II, which is basically a concrete blob. The sculpture suggests a concretizing of a durational movement. There have been multiple efforts to make this digitally with real movement. The process produces something called a motion sculpture, where objects in motion are recorded spatially and the movement’s “frames” or instances are conjoined together (a blob) into a digital asset or a 3D print. The test digital print that was created resembled a fossil. I thought it was a nice way to represent the concept of the flow of time and how it entangles the persistent analogization of time with space and space with time. The project was up in the air until I started talking to you about Palissy again.

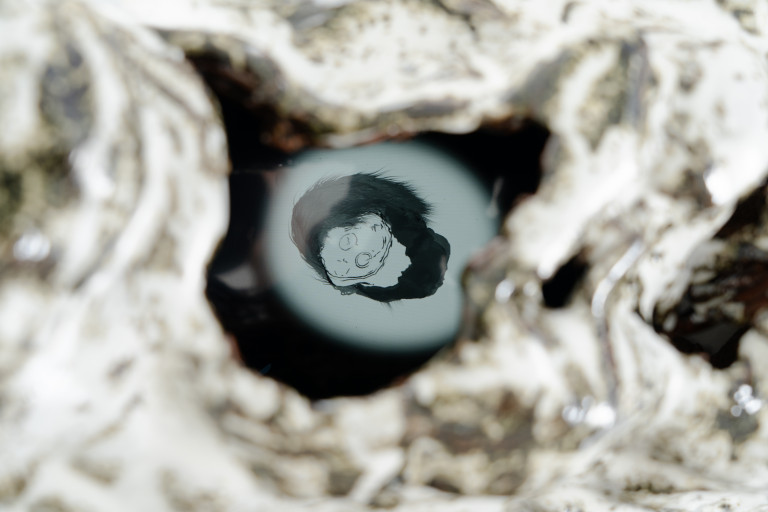

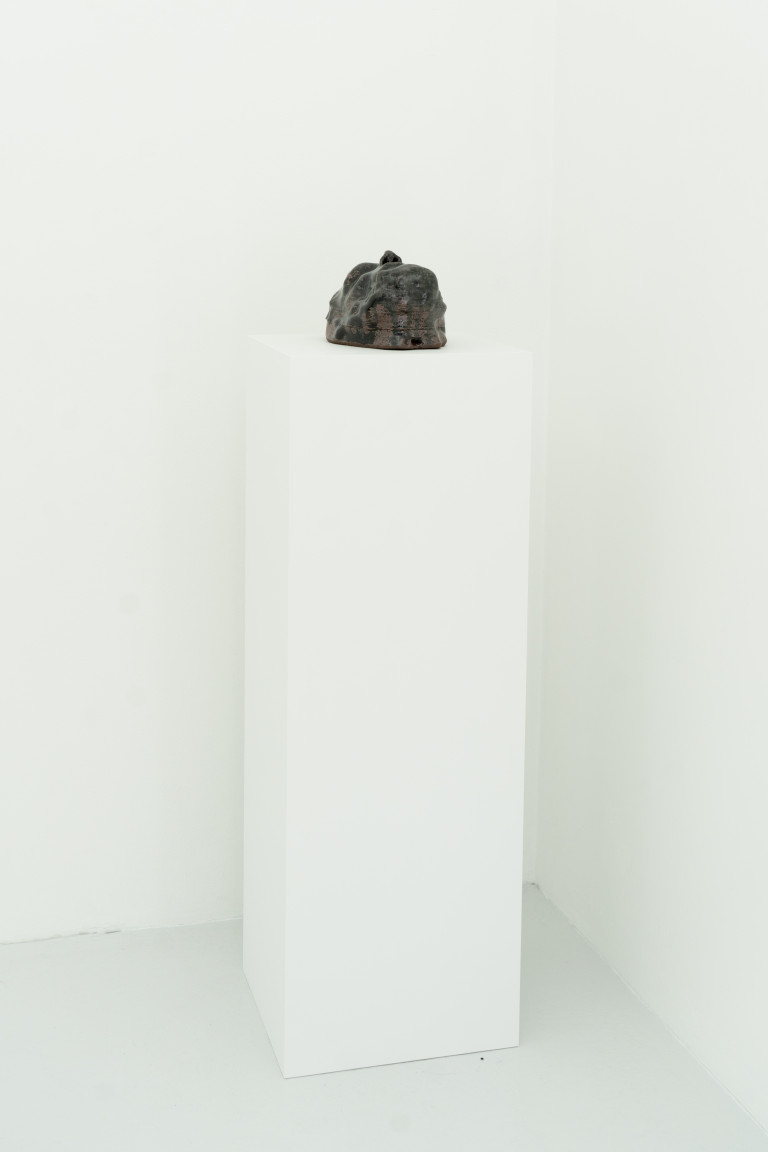

This John the Baptist head is based upon Rodin’s sculpture at the Norton Simon Museum. Scanned through photogrammetry and 3D printed in clay, the head is removed from its body and simulated in 3D software to fall and bounce. Again, this movement is depicted in solid form through joining of the instantiations of the head in different “frames” during the animation of the simulation. Depiction of time is collapsed and pressed into a ceramic form. An animation called “History Awaits Immanence” is shown inside the model on an LED screen. The line drawing animation, based upon a similar digital simulation, presents John the Baptist’s head rolling in perpetual loop.

Looping cycles, the ouroboros, and the mise en abyme, these are all things we share a love for. How do these forms express themselves through you?

CL: I think in some ways we have overlaps in our interests: the blurring of animacy in life forms and upending of that inanimate/animate hierarchy, and a contemplation of cycles of transformation of matter and role of decomposition and rot within those transformations. This also led me to a whole fascination with Louis Pasteur and the history of bacteria, virology, and hygiene. Particular relevant examples in the past were works about putrefaction in 2015 and 2016 and about spontaneous generation, the 17th century idea that life can begot from inanimate combinations of matter. The sculptures were based on Jan Baptist van Helmont’s “recipes” for spontaneous generation, such as two bricks with basil in the heat make baby scorpions, a dirty shirt with wheat makes baby mice. They looked kind of like Arte povera sculptures but were connected to a tincture (of scorpions and of baby mice) that visitors could ingest, completing the cycle of matter mingling.

I think I was interested in the way that theories of spontaneous generation radiate a queer potential, a model of kinship and reproduction that is intra-species and indifferent to gender or sexuality. Inanimate matter like bricks and plant matter like basil are all that’s needed to bear life. This challenges both the primacy of the heterosexual family model of reproduction, and the idea of kinship being only within one’s own species, and gives a world view that reconsiders the way human life is entangled with other species of life and other scales of time.

MR: Maybe we can end with a description of a half-imagined project inspired by Putrefaction? We start by motion scanning dancers dressed like other non-human animals. Combining that with digital animal forms scanned from real life: a bird eats a worm, a snake eats a rat, a wolf eats a sheep. And so on. The dancers enact these scenes of consumption and merging. The motion sculptures of both animals actions are fused together and 3D printed in clay. These clay motion sculptures, the conjoining of two animal actions in life/death, would become building blocks for a ceramic grotto we produce. This would be an homage to Palissy’s own lost grotto that did not survive.

CL: That sounds great but after doing this project, I never want to 3D print clay again!