“If she had any credo as an artist, it was to show us ourselves, and herself, even when it was dangerous to do so,” Hilton Als wrote of the late painter Alice Neel, known for portraits of friends and family and lovers, of artists and activists, made from the 1920s into the 1980s. Like Neel, Jiab Prachakul (b. 1979, Nakhon Phanom, Thailand) portrays members of her extended community not through a lens of literal danger, or even resilience, so much as a posture of strength that rests within the vulnerable act of sharing one’s interior self. In her new paintings, the artist focuses on people who give her the sense of pride and support to move forward confidently in the world, as she is. “To move forward,” Prachakul says, “is to know where you came from, where you are now, and where you want to go next.”

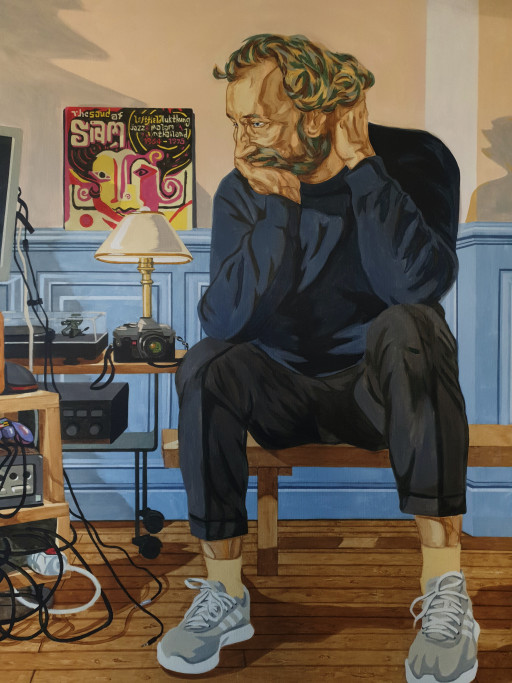

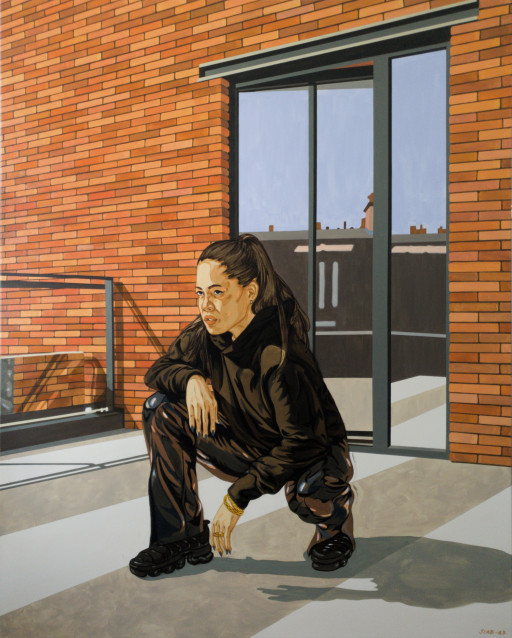

For the artist, depictions of friends and frequent sitters inform and reveal her own being. They are not self-portraits, but rather, works about seeing the self through another. A portrait of two German-Japanese sisters—who Prachakul met at a ramen house in the twins’ hometown of Berlin—opens onto the lives of individuals who, like the artist herself—currently based in Vannes, Brittany, France—are often part of the global Asian diaspora. Within the genre of portraiture, which establishes the importance of an individual and traditionally disregards diasporic experience, Prachakul brings into cinematic focus subjects who are often caught, ever so slightly, off camera. Disguised in sunglasses or a trench-coat, or pictured in a downward glance, lost in thought, sometimes eyes slightly emptied with an awareness of being watched, her sitters gain the agency to be seen not by a hierarchical gaze, but to be seen as a peer, to look to each other, to their families and companions, to the eye of themselves.

Echoing the show’s title, her portraits reflect both the simplicity and complexity of identity as Prachakul combines forms at once summarized and detailed. What does it mean to condense someone? Is flattening about gesturing to an essence, or about the ways society glosses over our crevices to conform to its expectations? In the almost graphic quality of her works, a kind of flattening functions to spatialize different dimensions of selfhood as they start to cohere. Or, perhaps, speaks to the compression of time in knowing a person at different life phases.

Prachakul engages a distinct mode of image-making that suggests how individuals are shaped by but also exceed or evade confining categories of identity as stereotypes and stigmas would prefer to have it. A sitter slumps shirtless on a dining room chair in showing a range of tattoos on his torso, which, the artist explains, would be considered taboo in public places in Japan. One tattoo reads: “You Exist, Therefore, I Am.” In these studied but fugitive moments, almost fragile in their immediacy, a cheek sinking into the support of a hand, her works become a kind of hyphenation: “both-and.” An argument for the ways in which we are always both observers and subjects, unfolding together. A quiet rally against traditional portraiture’s cemented, inert archetypes—coaxing out the ways the self is determined through singular experience but also overlaps and recognition of shared humanity.

–Margaret Kross