Fiza Khatri, Confidant

Micki Meng, Chinatown

May 30 – July 18, 2024

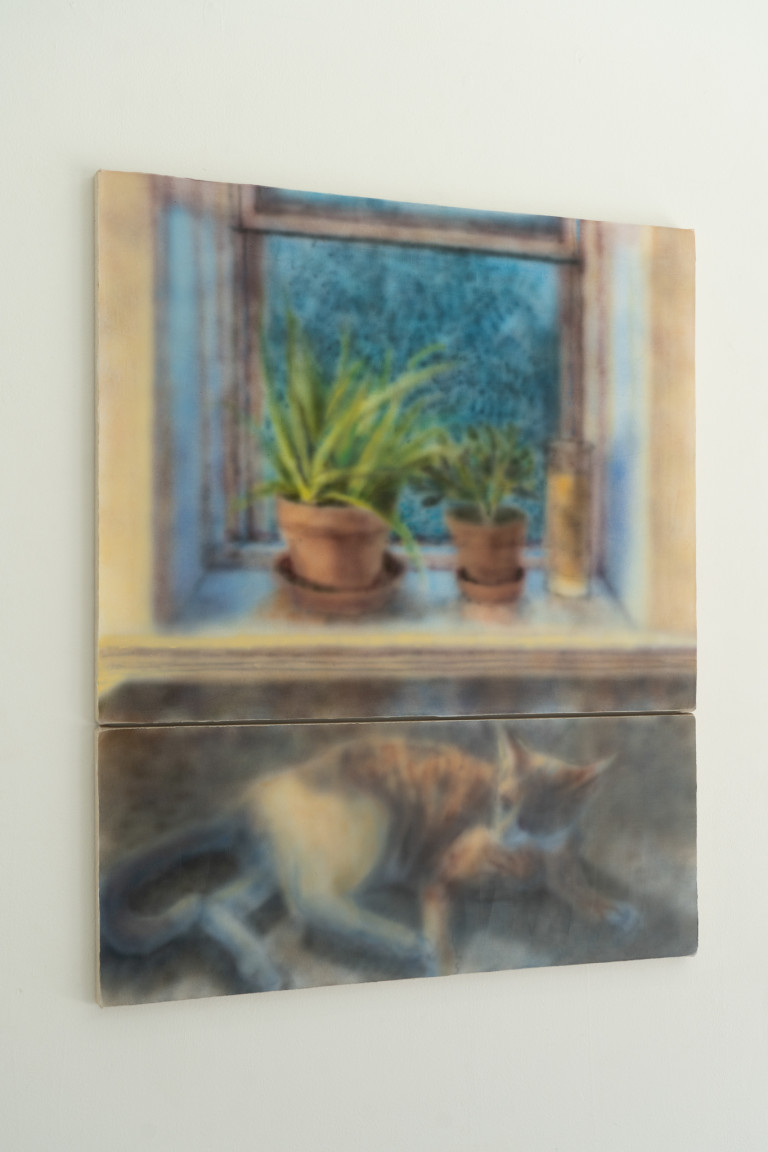

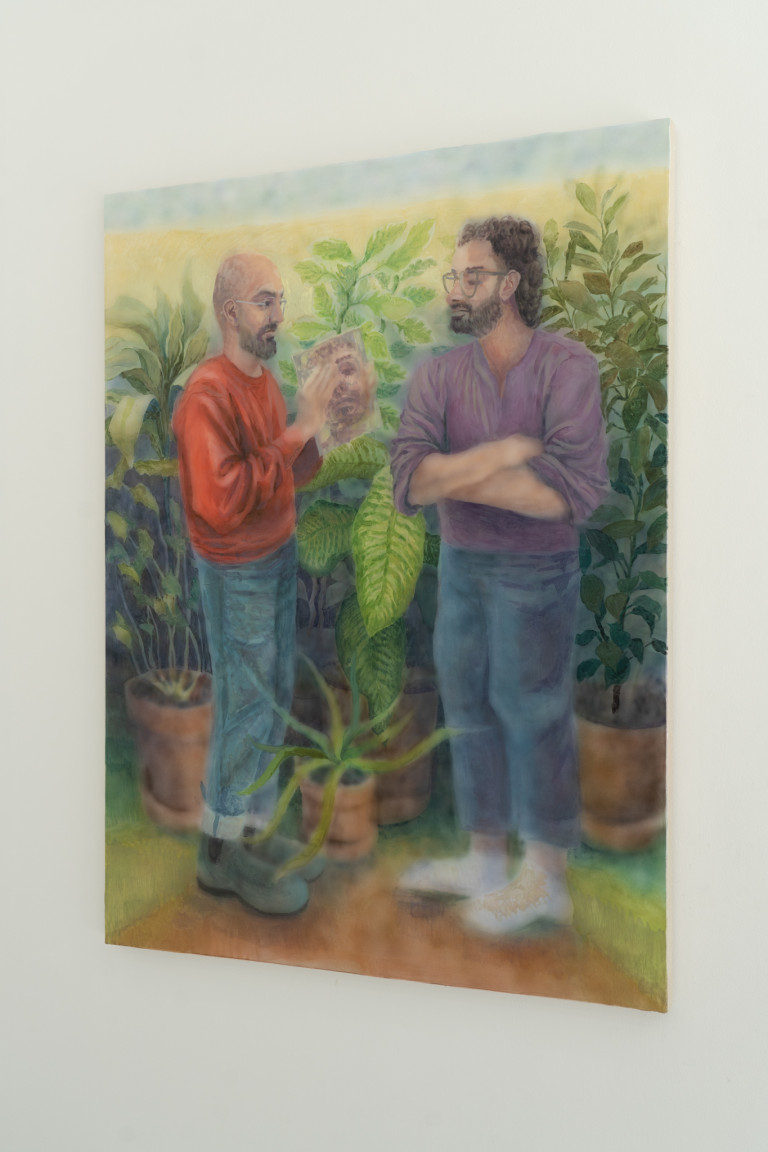

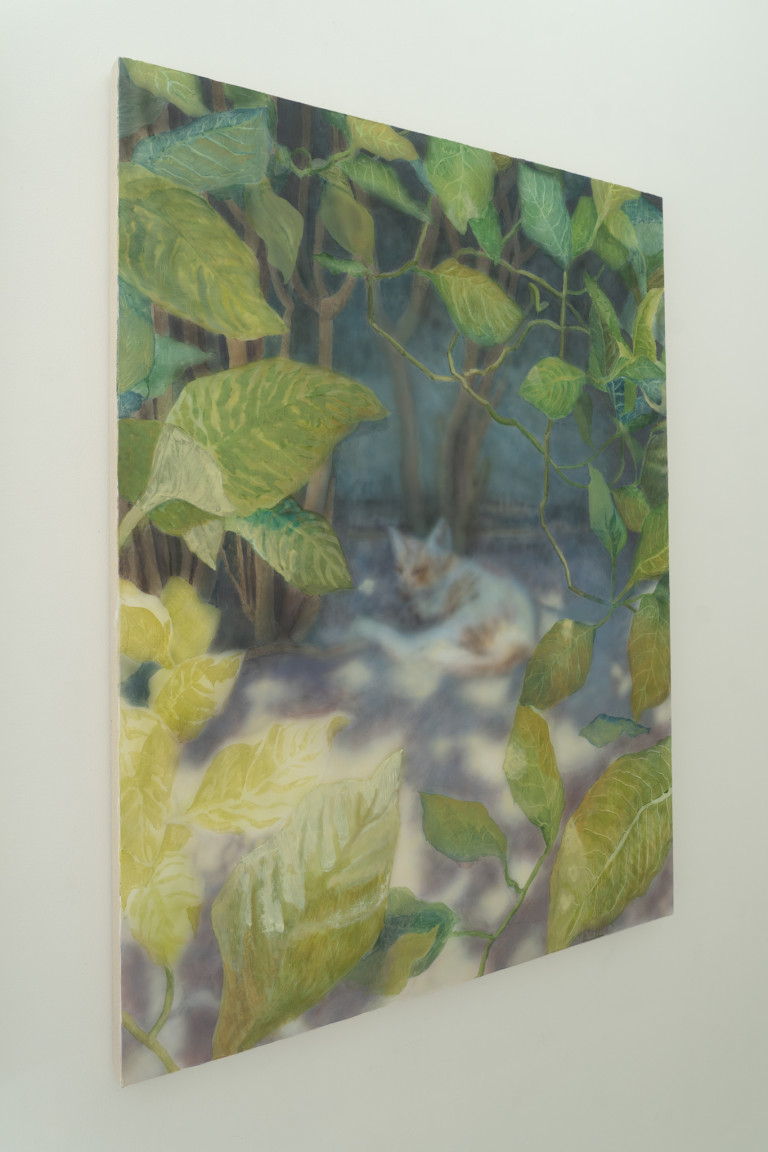

Shivering in and out of focus, Fiza Khatri’s Confidant configures a series of paintings that treat the interior as exterior and vice-versa. Sharpened vines frame the softened shape of a cat seeking respite from the sun. A hazy figure stretches while inter-twined with potted houseplants whose containers and leaves reach forward with rendered clarity. The background/foreground dichotomy so familiar in the Western canon of painting is forgone in favor of a wash between the two. The technique describes a sense of memory – the periphery of a feeling.

The Sanskrit word rasa roughly translates to flavor, juice, or nectar. Fiza tells me that this word here refers to an emotional essence, which is relayed through both space and figure. A kind of friction and harmony that is evoked by the entire composition of bodies and their environments conveys this essence. They are co-determinants, confidants, one defines the other – the message of the work can be found here. It is storytelling, but not in the narrative sense.

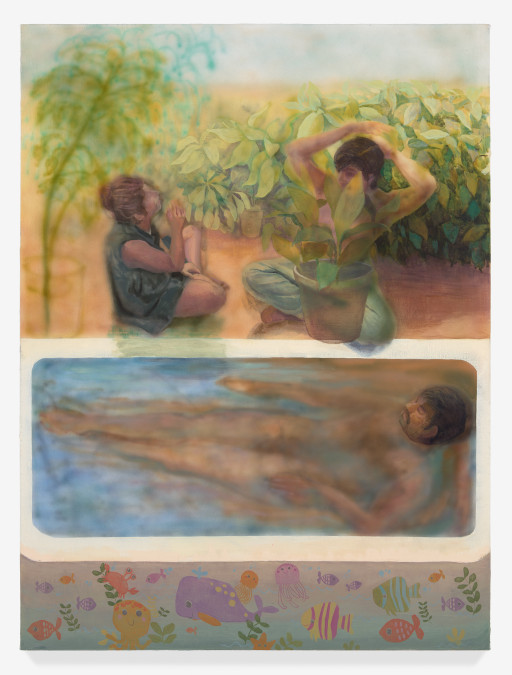

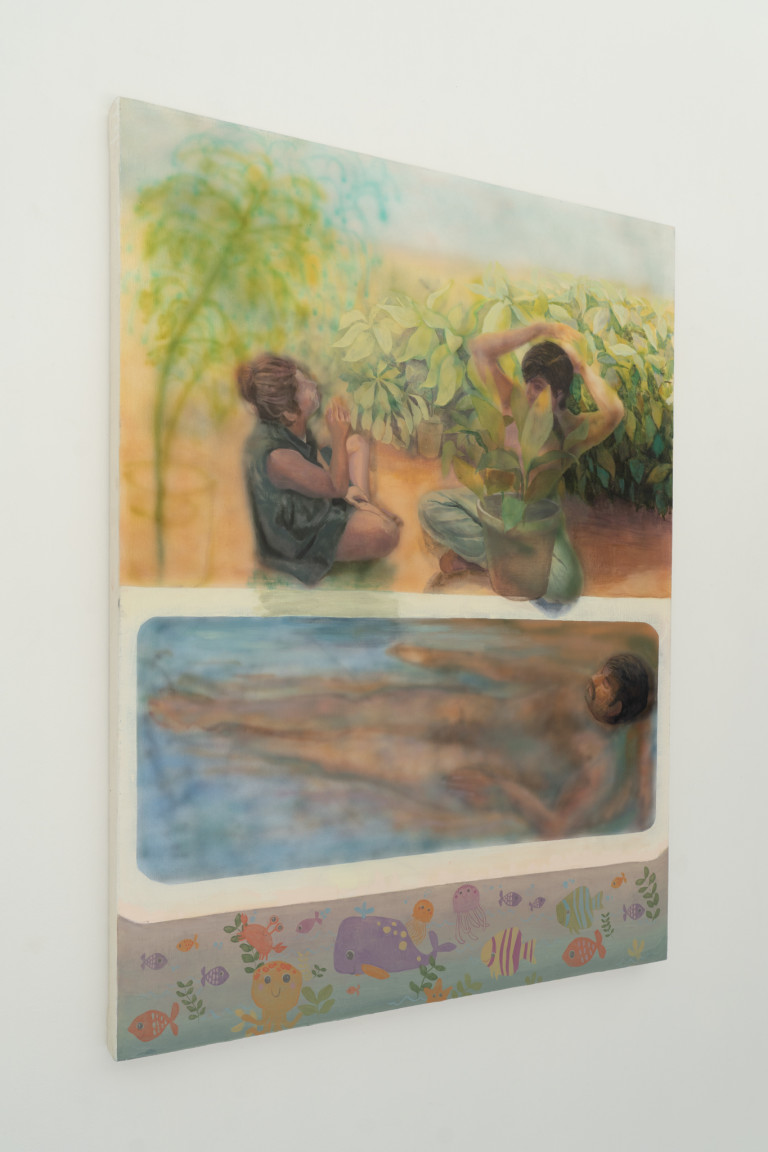

As a central reference in this series of works, Khatri looks to Rājput painting which is a genre of miniature painting that emerged from the independent Hindu states in feudal India throughout the seventeenth century. Distinguished by its more romantic style, Rājput miniatures treat figure and ground as complete narrative harmony. Space is flattened dramatically so that the Punjab hills and the characters within them are of the same depth – the same importance, compositionally. In Bather with Friends, a sort of triptych is constructed where two figures converse in a natural environment atop a bather half-submerged in a bathtub hovering over a child-like motif wallpaper. Community, repose, play. Stacked in this way a sensation is outlined, one of deep familiarity that gives way to an ease of being in one’s own skin. This is itself a form of being at peace with one’s environment.

Decoration also describes a union between what is internal and one’s surroundings here. In the South Asian art and literature that Khatri references, adornment is not understood as merely additive. What we are accustomed to seeing as frivolous, topical, or even suspicious in America’s dominant version of contemporary life is reinstated as a proposal to reach a freedom within our contexts. For example, within Sufi poetry, the decorating of the self (the ritual of dressing) is framed as a preparation to meet a beloved. This could be the meeting of a lover, but it also could be god, unity, or even one’s own being. When light dances on a table adorned with an overflowing bouquet of roses in, to be titled, decoration is expanded, and becomes a metaphor to speak about training the spirit, body, and soul to be in harmony with the world.

Throughout Confidant, content leans on the surface. It insists on its importance and allows it to be released from a paranoid reading of something lying underneath. In these works, looking to the past, obscuring focal views, and insisting on containers of beauty dignifies even the most quiet moments of existence.