Dear Candice,

When I first set eyes on your cat paintings in late June, I exclaimed, “Who made these?” It was a foolish question in retrospect, because I probably actually knew the answer to my own question before it left my masked mouth, but perhaps it’s worth explaining why I was a fool for (at least) that hot moment.

First, the paintings were in your studio, and there were too many of them there to assume they were the work of someone else, received as a gift or acquired in a trade. They were almost hiding, but in plain sight, as if they were not intended to be seen but secretly asking to be seen! I had just entered your studio for a brief moment to see something else, a large ceramic work, and in fact the reason I had ventured to see you was to return a borrowed book, long overdue, and to take another in exchange. It was my first and only studio visit during COVID times. Your studio is so dense with stuff, richly layered with so much sense data—art works, yes, but also materials and objects of research, visual, tactile, olfactory—and I was initially overcome with the potent odor of the rotting remains of a recent work. A few of the paintings in question were hanging on your wall of storage shelves; more were stacked and sitting on the floor below.

Second, they all feature cats. Cats and people, but the cats should have been the tipoff. The last time I saw you in real life, in fact, was at the opening of your exhibition at Pitzer College (Natural History: A Half-Eaten Portrait, an Unrecognizable Landscape, a Still, Still Life, 2020), a show cut short by the virus, which featured a stunning terracotta sarcophagus with life-size figures of you and your “future cat”: Death was already on your mind, ahead of the curve. Your fondness for felines is well known, certainly to me, as your correspondence often includes updates about Roger, the cat with which (whom?) you co-habitat. And I also knew about White-n-Gray, aka WG, a feral friend who frequently visited, but had recently stopped coming to eat the food you’d leave for him on your porch. Your recorded eulogy for WG—a story told from WG’s vantage, in which you are hilariously referred to as “the Fleshlumps”—is a moving tribute to a complex, often asymmetrical relationship. Cats had also appeared in other of your works in recent years, including cat masks made from pressed tobacco leaves—one of which was hanging near these paintings.

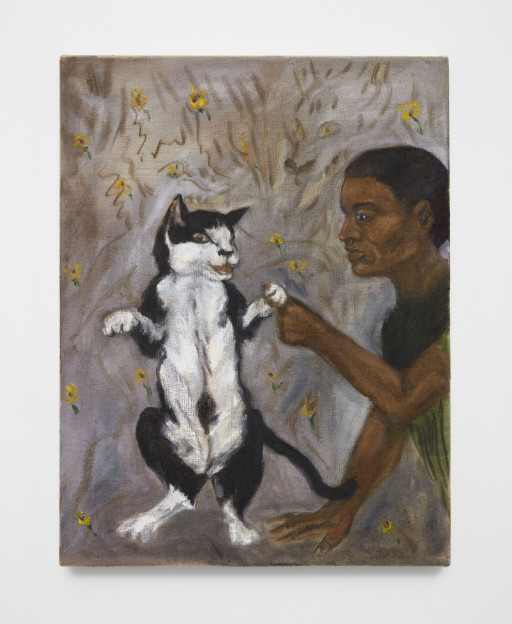

Paintings: This was perhaps the biggest stumbling block for my brain. And despite your wide latitude for materials, I’ve never imagined you making a painting, by which I mean an honest-to-goodness-stretched-canvas-slathered-with-pigment-suspended-in-oil-by-means-of-a-brush painting. Despite the rather extraordinary range of your materials—from clay to mushrooms to drawing to video to cochineal to tinctures to cast tin to silk worms to urine to sound—I could have never imagined you making something as conventional as a painting. And by convention, I mean European. These cat paintings were downright modernist, which was more typically the subject of your critique than your mode of exploration, and I must admit it confused me, pleasingly. These were interior paintings, cats and people mostly in slow motion if not repose, seemingly immobilized, as we all have been, by the new rules imposed by the plague. I detected hints of Vuillard (Vuillard? Candice?) in the overwhelming, even suffocating ornamentation of these interiors, in which the wallpaper might swallow the figures alive. One of these paintings featured a smug Oscar Wilde (“sort of,” you said) character; another, a deathbed scene, was an explicit homage to Max Beckmann’s Great Scene of Agony (1906). The latter matched the dread of the original, but added two cats—three if you count the gigantic whiskered face submerged in the blood red wall that holds the scene—attending to the transition from life to whatever might come next. (These quietly conjure Lokapala—hybridized cat-human guardians of the Tang dynasty, which also appear more conspicuously in your ceramics.) Another more recent homage, drawn on your new iPad, replaces Mantegna’s dead Christ with a frisky cat, lying belly-up, daring a belly touch.

In addition to the great interiorists Vuillard and Bonnard, the latter of whom often painted cats, I also considered a wild range of likeminded feline enthusiasts. Joan Brown immediately sprang to mind, especially given the San Francisco context of the coming show, but especially Carolee Schneemann. Who needs to read Haraway’s dog-centric Companion Species Manifesto when they can instead marvel at Schneemann’s Infinity Kisses (1981-7), a series of photos of the artist lavishing affection (with tongue) upon her cat Vesper after it woke her each day? “THE CAT IS MY MEDIUM,” Schneemann once declared, emphatically, and indeed cats appear throughout her expansive body of work, from a drawing done at the age of four (The Exuberant Cat, 1943), to a five-hour film of her cat Kitch (Kitch’s Last Meal, 1973-76), to a gruesome photograph taken of her just-dead “magical cat” Treasure, one of its eyes popped out of place. “That’s part of my need to look at things that we don’t want to see,” Schneemann responded to viewers horrified by the image. “You can all close your eyes, but I don’t.” For me, that line resonates with your ferocious attraction to bugs and stinky stuff, but also to the brutal and appalling episodes of colonial history, all of which your work routinely challenges us to look at, too.

But these cat paintings do something else… perhaps! For the viewer, but also, I think, for you. They are playful and curious, cat-like, but when you claimed them in your studio that day, I could tell that they also made you slightly nervous or possibly embarrassed, which was both endearing and surprising. Because I have often found myself in awe of your fearlessness, which most often manifests as artwork that doesn’t look or work like any art work I’ve seen before. That’s intended as a compliment. I think it’s good when artists get nervous or embarrassed about their own work. (Writers and curators too.) There is great care in these paintings, in their touching (literally and metaphorically) subject matter, and in your self-education in this strange, old medium. Your rendezvous with oil and canvas (well, encaustic and linen) and the Western canon is a quarantine fever dream—claustrophobic (all those interiors, all that art history!) and delirious. These are surely paintings of mourning, with empathic thoughts for your departed feral friend but presumably for all of us waiting out this awful purgatorio.

The more recent paintings, including the ones we plan to show at Friends Indeed, are gradually becoming lighter—in touch if not also in mood. There are obvious exceptions—At the Death Bed, in particular, shoulders the heavy burden of our moment. It is also the one painting where the cat nearly disappears from view. But Dance with Me is light, jubilant—at least for Roger if not so clearly for the person he’s dancing with. I think it’s important to emphasize that the “friends” who appear in these paintings (with your father as one notable exception) are mostly figments of your imagination, even as they conspire with real cats drawn from your world. In doing so, you remind us that painting is and has long been a space for ideation, a surface for projecting one’s imagination. Jealousy does this with great subtlety—an Asian man strokes White-n-Gray under the chin, as Roger looks on with envy. In reality, WG would have never put down his guard and assumed such a vulnerable pose. During this present pandemic, perhaps we are all jealous of those who can let their guard down for a gentle stroke under the chin. When looking at this painting, I’ve variously imagined all three figures—the stroker, Roger, WG—all as stand-ins for you. (You don’t visibly appear in these paintings, but you are inevitably in them.) With our fraught new relationship to other humans—strangers and friends alike—there is undeniable comfort in animals. I can only imagine Roger has been very happy to have you home so much in recent months. He is also blissfully oblivious to the folly of humankind. Or at least I hope that’s the case.

There is so much more I could say about these strange and wonderful paintings—and the ceramics too. I’m so happy we have an opportunity to show them. I am writing this letter in lieu of a press release, but also in hopes of perpetuating our ongoing, intermittent epistolary exchange, which is most often kept private between us but is sometimes offered up for wider delectation, with a little nervous embarrassment.

With distanced affection,

Michael

Candice Lin (b. 1979, Concord, Massachusetts) works in Altadena, California. She received her BA in Visual Arts and Art Semiotics from Brown University, in 2001, and MFA in New Genres from San Francisco Art Institute, in 2004. Her practice utilizes installation, drawing, video, and living materials and processes, such as mold, mushrooms, bacteria, fermentation, and stains. Lin has had recent solo exhibitions at the Govett Brewster Art Gallery, New Zealand; Walter Phillips Gallery, Banff Art Center, Canada; Bétonsalon, Paris; Portikus, Frankfurt. In 2021, she has upcoming solo exhibitions at the Walker Art Center, Minneapolis; Times Museum, Guangzhou, China; Spike Island, Bristol, United Kingdom; and the Carpenter Center for the Visual Arts, Harvard University. Lin’s work is included in the upcoming Prospect 5 Biennial, Louisiana; Gwangju Biennale, South Korea; and was part of the 2020 Ashkal Alwan Home Works 8 Forum; 2019 Fiskars Village Art & Design Biennale; 2018 Taipei Biennale; the 2018 Athens Biennale; Made in L.A. 2018, Hammer Museum, Los Angeles; New Museum, New York; and Sharjah Biennial 2017, Beirut, Lebanon. She is the recipient of several residencies, grants and fellowships, including the Joan Mitchell Painters and Sculptors Grant (2019), The Artists Project Award (2018), Louis Comfort Tiffany Award (2017), the Davidoff Art Residency (2018), and the Smithsonian Artist Research Fellowship (2009). She is Assistant Professor in Art at University of California, Los Angeles.

Michael Ned Holte is a writer and independent curator based in Los Angeles, and a member of the Art Program faculty at CalArts. He previously collaborated with Candice Lin for the exhibition Ours is a City of Writers at the Los Angeles Municipal Art Gallery in 2017. His previous curatorial projects include Routine Pleasures (2016) at the MAK Center for Art and Architecture at the Schindler House, Los Angeles; TL;DR (2014) at Artspace, Auckland, New Zealand; and Made in L.A. 2014 (with Connie Butler) at the Hammer Museum, Los Angeles. He is currently organizing the exhibition how we are in time and space: Nancy Buchanan, Marcia Hafif, Barbara T. Smith at the Armory Center for the Arts, Pasadena, opening in 2021.

Candice Lin (b. 1979, Concord, Massachusetts) works in Altadena, California. She received her BA in Visual Arts and Art Semiotics from Brown University, in 2001, and MFA in New Genres from San Francisco Art Institute, in 2004. Her practice utilizes installation, drawing, video, and living materials and processes, such as mold, mushrooms, bacteria, fermentation, and stains. Lin has had recent solo exhibitions at the Govett Brewster Art Gallery, New Zealand; Walter Phillips Gallery, Banff Art Center, Canada; Bétonsalon, Paris; Portikus, Frankfurt. In 2021, she has upcoming solo exhibitions at the Walker Art Center, Minneapolis; Times Museum, Guangzhou, China; Spike Island, Bristol, United Kingdom; and the Carpenter Center for the Visual Arts, Harvard University. Lin’s work is included in the upcoming Prospect 5 Biennial, Louisiana; Gwangju Biennale, South Korea; and was part of the 2020 Ashkal Alwan Home Works 8 Forum; 2019 Fiskars Village Art & Design Biennale; 2018 Taipei Biennale; the 2018 Athens Biennale; Made in L.A. 2018, Hammer Museum, Los Angeles; New Museum, New York; and Sharjah Biennial 2017, Beirut, Lebanon. She is the recipient of several residencies, grants and fellowships, including the Joan Mitchell Painters and Sculptors Grant (2019), The Artists Project Award (2018), Louis Comfort Tiffany Award (2017), the Davidoff Art Residency (2018), and the Smithsonian Artist Research Fellowship (2009). She is Assistant Professor in Art at University of California, Los Angeles.

Michael Ned Holte is a writer and independent curator based in Los Angeles, and a member of the Art Program faculty at CalArts. He previously collaborated with Candice Lin for the exhibition Ours is a City of Writers at the Los Angeles Municipal Art Gallery in 2017. His previous curatorial projects include Routine Pleasures (2016) at the MAK Center for Art and Architecture at the Schindler House, Los Angeles; TL;DR (2014) at Artspace, Auckland, New Zealand; and Made in L.A. 2014 (with Connie Butler) at the Hammer Museum, Los Angeles. He is currently organizing the exhibition how we are in time and space: Nancy Buchanan, Marcia Hafif, Barbara T. Smith at the Armory Center for the Arts, Pasadena, opening in 2021.