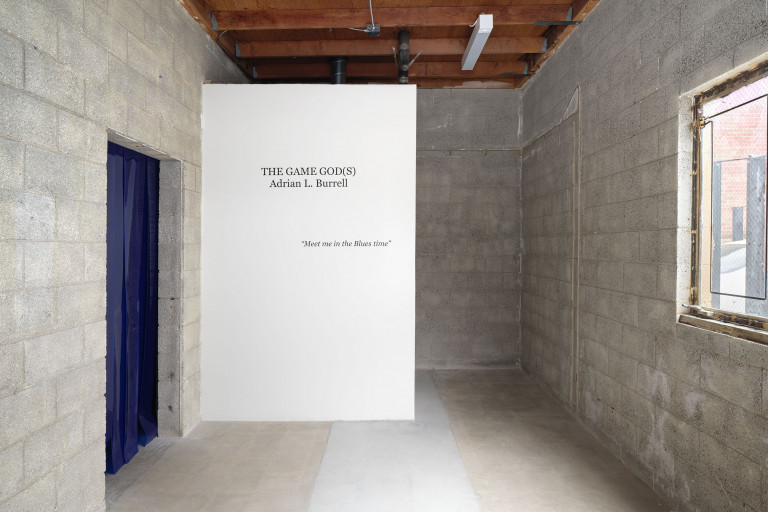

Micki Meng debuts a Los Angeles off-space with Adrian L. Burrell’s The Game God(S), open May 23 through June 30, 2023.

5831 Perry Dr

Los Angeles, CA 90232

Open Wednesday—Saturday, 12—6 PM

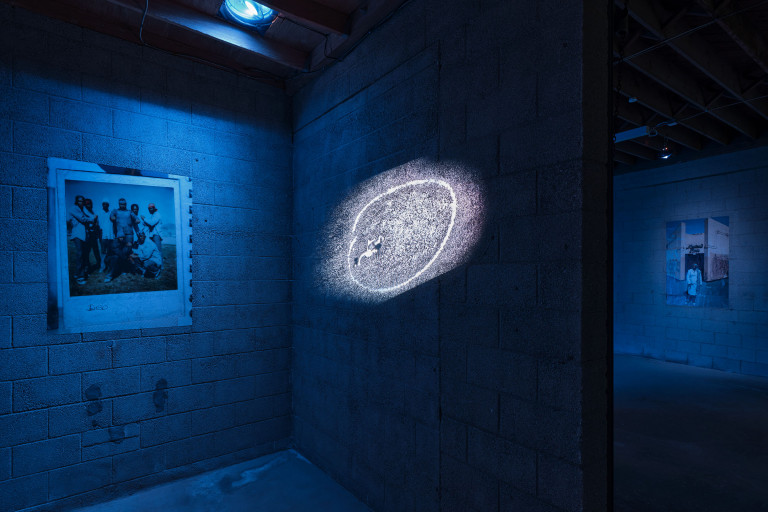

In Burrell’s film, The Game God(S), mythology, documentary, and archival study form a choir of methods from which an analysis of anti-Black capitalism and the treachery of progress accumulates across the body like salt. We are not cleansed but reminded of a history that builds up with the restless ebb and flow of endurance and sorrow. In conversation with the methodologies of Khalil Joseph, Dr. Bedour Alagraa, Dewey Crumpler, and Dr. Ayodele Nzinga, Burrell’s filmic language firmly situates itself within contemporary discourses on Black filmmaking, poetry, portraiture, painting, and critical theory. The film is a vibrant and dire exploration of the anti-Blackness cardinal to capitalism which severs Black social bonds, coerces Black populations into modes of living perpetually vulnerable to carceral force, and the relentless emergence of social life in the face of social death. The wax and wane of the tide, or the film’s cutting to and fro different landscapes of struggle, becomes an analogy for capitalism’s economic relations, which, much like, and precisely by way of, the sea, are inextricable from the groans which haunt their shared abyss. Burrell’s filmic approach briefly attends to, without pathologizing, the multifarious ways in which survival is burdened by the flow of carceral time. Blackness, as Burrell elucidates, is not afforded the linearity of history, the ascendancy of progress, nor the synthesis of memory; it knows endurance through a language of rupture, repetition, and perhaps retribution.

The film (dis)embodies the historical preclusion of Blackness from our overrepresented Western model of time; oscillating between the brief accounts of Martina, Frank, Brianna, Craig, and The Goddess of the Crossroads (performed by Dr. Ayodele Nzinga), the film articulates a Black(ened) experience of time, a roulette of perils indiscernible from possibilities. Each vignette cunningly points to, without recourse to any explicit depictions of violence, what one must endure or what one has lost in an attempt to weather the pernicious waters of modernity as that most vulnerable to the forces of its inception: the Transatlantic Slave Trade. The Game God(S) distills the unsayable and ongoing condition of being property or the world-historical quality of being the party not party to everyday legal, social, symbolic, and economic exchange. Instead, we see Black bodies exchanged between prisons, judicial processes, illicit markets, and criminalized forms of survival. The vignettes invoke “the burdened individuality of [so- called] freedom” theorized by Saidiya Hartman. Blackness is granted fantasmatic mobility on the condition that it does not interfere with the operations of the Game, which renders it always available to the predatory will of carceral capital. We are reminded that Blackness has been fashioned into that which is exchanged such that the American Dream can come into being. Burrell’s film then broaches the question: what does one, who endures capitalism as its psychic, material, and symbolic commodity, do to survive? How does one make a way out of no way?

The Game God(S), paradoxically dream-like in its form but all too real in its content, imparts something crucial about the interpretation of this (American) dream. That it is a game, as the Goddess of the Crossroads foretells, which may be “fatally flawed.” She wants to know something, a final question, insofar as it remains the question at the end of discourse: “How long before we clear the board altogether?” The Goddess poses this question with a harrowing laugh, followed by a grimace filled with categorically justified rancor which calls upon us to know the answer by now—indeed, some of us have known it all along. As Burrell tells us, this film “doesn’t allow for simple endings.” Ambiguity is both a tactic and object for Burrell. It is another affect, much like time, that is caught up in the dynamics of capital afforded to the Western subject who ironically finds consolation in the struggle to predict its future. “The children of the Sun” have always known what capitalism has in store for them, for us. The Game God(S) holds us in the Hold. It calls us to drift with its questions; lingering like ash weeping from a fire we have yet to quell—precisely because if it goes, capitalism goes with it.

— Boz Deseo Garden